The Taiwan Offshore Wind Industry and Fishery Industry under the Net-Zero Goal

The Taiwan Offshore Wind Industry and Fishery Industry under the Net-Zero Goal

In early March 2022, the wind farm projects that have recently applied to join the Round I zonal development bidding have entered environmental impact assessments (EIA). At the end of the same month, the National Development Council (NDC) announced Taiwan's Pathway to Net-Zero Emissions in 2050, setting the short-term and mid-term (until 2030) development goal of “Increasing Self-Generated Renewable Energy” and the long-term (until 2050) development goal of “Maximizing Self-Generated Renewable Energy.” The total installed capacity is estimated to reach 20.6GW in 2035 and 40~55GW in 2050.

How much sea area is required for 40GW? Do we have enough sea area? Here's an even more basic question, can the marine environment bear such an intense amount of wind farm development? If we assume that: (1) the 9GW offshore wind farm projects of phase I zonal development (grid connection in 2026~2031) are within the territorial sea (reference 1) , and the offshore wind farm development zone after 2032 is limited to the exclusive economic zone (reference 2), meaning 25.4~40.5GW will be constructed, and (2) the density is 1GW every 100km2, the required area would be 2,540 ~ 4,050km2.

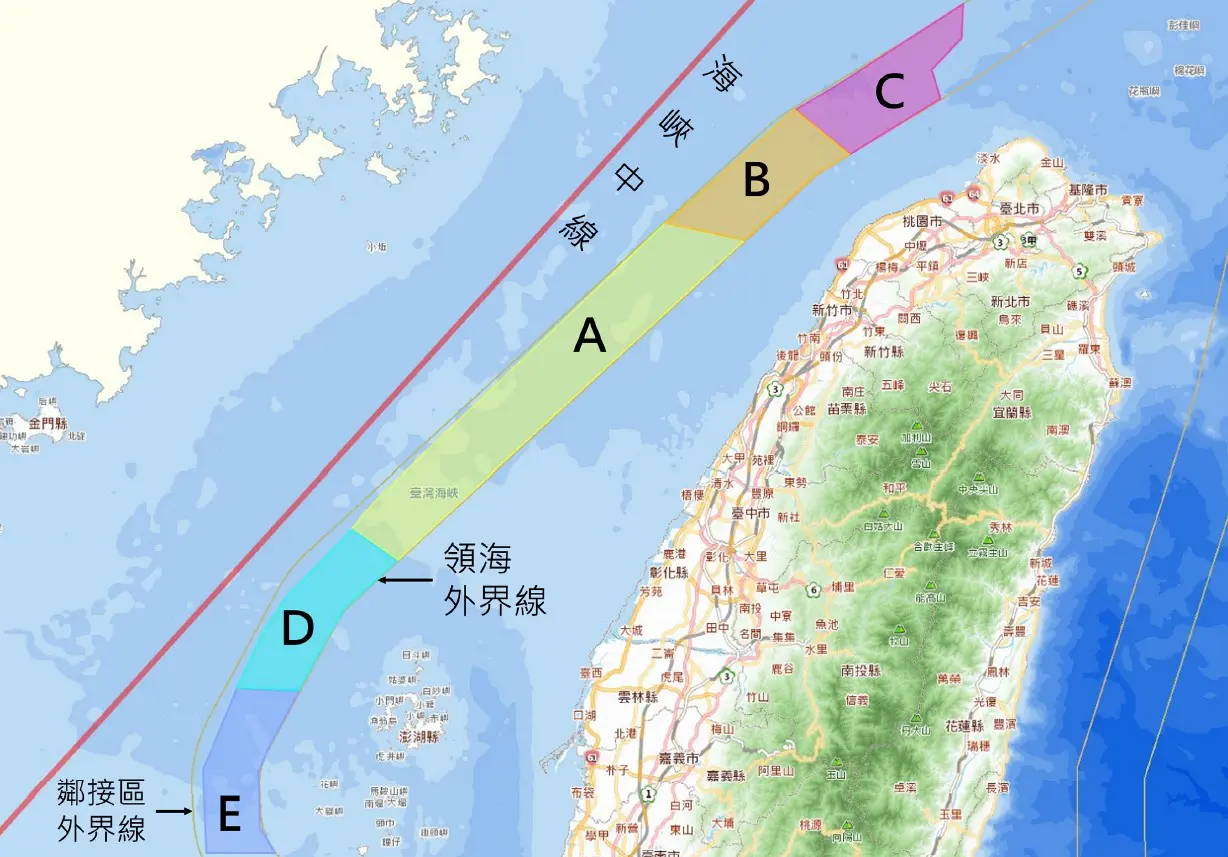

After taking the distance between the wind farms, the international and cross-strait shipping lanes, subsea pipelines, military restrictions, and other issues into consideration, the result is the demand for 7,000 km2 of sea areas in the contiguous zone of Taiwan Strait, which is equivalent to the distance from Cimei in Penghu, all the way to the west of Pengjia Islet, surrounding most of the western sea area of Taiwan (refer to Fig. 1).

Figure 1: 7,000 km2 of sea areas in the contiguous zone of Taiwan Strait are marked. Area A is 3,000 km2, while the rest, namely B, C, D, and E are all 1,000 km2 each.

Source of the base map: The Integrated Sea Area Information Platform: https://ocean.moi.gov.tw/Map/.

Taiwan Strait is not only the traditional fishing ground for domestic fishermen but also an area with a massive presence of Chinese fishing boats. When a large number of offshore wind farms overlap with the fishing ground, the fishing operations would be impacted, which would not only affect the offshore fishermen's livelihood but also endanger national food security. Although the continental European countries have set the North Sea offshore wind farm area as a non-fishing zone, this method cannot be applied to the small and narrow-shape waters of the Taiwan Strait. We are facing a more urgent need to implement multiple uses of the ocean.

Reference:

1. Renewable Energy Development Act, Article 3: "6. Offshore wind power system: Refers to energy generated from wind power is converted into electricity with offshore wind farm installed in waters outside the subtidal line and not exceeding the bounds of the territorial sea."2. Law on the Exclusive Economic Zone and the Continental Shelf of the Republic of China, Article 5: "The Republic of China shall, in its exclusive economic zone or on its continental shelf, enjoy and exercise the following rights: 1. Sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring, exploiting, conserving, and managing the resources, living or non-living, of the waters superjacent to the seabed and of the seabed and its subsoil." Article 7: "For utilizing energy from the water, currents, and winds or other activities in the exclusive economic zone of the Republic of China, permission from the Government of the Republic of China shall be required. The related permission regulations shall be decided by the Executive Yuan."

EIA is the only gatekeeping mechanism

Unlike the approach of " Verbot mit Erlaubnisvorbehalt (prohibition in principle with permits as exceptions)" adopted by the continental European countries and the UK regarding their offshore wind farms development, Taiwan has never seen legislation for marine space management in decades. The Bureau of Energy has always adopted the approach of "permission in principle with prohibitions as exceptions" for the potential sites of phase II, which allows the developers to plot the sea areas to be developed by themselves. Due to the lack of overall preliminary planning, the case-by-case EIA has become the only channel for other parties to join and supervise.

The Environmental Impact Assessment Act has listed 10 development activities, whereas Article 41 - 56 of the "Regulations on the Environmental Impact Assessment of the Development Behaviors" stipulate the assessment items for different development activities. However, offshore wind and similar development activities were not mentioned in these laws and regulations. For instance, offshore wind farms are developed in spots, and although the area occupied by the entire wind farm is extremely huge, there is high potential for the co-existence of other activities in the same sea area, unlike how the development zone of terrestrial facilities usually leads to strong exclusiveness. One of the greatest differences between offshore wind farms and their terrestrial counterparts is that no residents live near the former, thus taking the coastal administrative areas and their residents as the "relevant authorities" and "local citizens" to be engaged with as required by the EIA regulations is indeed meaningless. Article 19 of the "Environmental Impact Assessment Enforcement Rules" requires the assessment of "Those circumstances in which the development activity has a significant adverse impact on the movement or rights of local residents or the traditional ways of living of minority ethnic groups." According to the definition of the law, without any residents nearby, no adverse impact will be identified. Nevertheless, reality implies that large-scale and dense developments of offshore wind farms and their affiliated sea lanes will result in the dilemma of offshore fishermen, who would find no sea area for their operations.

The cumulative effect is the most difficult part of the whole EIA process. As stipulated by Article 15 of the Environmental Impact Assessment Act, "For those circumstances in which two or more development activities are to be implemented at the same site, assessments may be jointly conducted." However, how can we define what projects are "at the same site" in the borderless sea areas? Are joint assessments compulsory or optional? Different companies may propose different development plans for the same sea area while claiming that there is no alternative plan, but from an overall national perspective, the different development plans for the same sea area are in fact the "alternative plans" for each other. The EIA committee members have only two options: to approve or not to approve. They have no right or responsibility to identify the development plan with the least impact on the environment and ecology, or the one with the sincerest engagement with stakeholders.

The core regulations have been neglecting the features of offshore wind farms, but the "Technical Specifications for Marine Ecology Assessment" (海洋生態評估技術規範) set by the Environmental Protection Administration (EPA) in 2007 according to the "Regulations on the Environmental Impact Assessment of the Development Activity" (開發行為環境影響評估作業準則) also have not seen any amendment in response to the newly emerged development activity. Furthermore, according to the definition of the core regulations, the EIA should include assessments of the living environment, natural environment, and social environment, as well as aspects of the economy, culture, ecology, and others. Still, the aforementioned technical specifications were narrowed down to "the assessment that involves marine ecology." In this sense, how will the socioeconomic aspect, such as the fishery economy, receive a proper assessment with the establishment of alleviation measures?

The possibility of co-existence

Apart from a comprehensive case-by-case EIA, Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) at the macro-view level and fisheries liaison at the micro-view level are also key roles in achieving the co-existence of offshore wind farms and the fishery industry.

Marine Spatial Planning refers to "the analysis of space and time of human activities in the marine area and the public discussion process for the distribution, both with the purpose of determining the approaches to achieve the ecological, economic, and social goals established during the discussions of policies." The driving force of the MSP can be divided into two types: economic and environmental. The European Union has established the Directive 2014/89/EU "establishing a framework for maritime spatial planning" in response to the growing demands of the marine spaces from the traditional and emerging departments while maintaining the normal operations of the marine ecological system. In terms of the MSP, the primordial goal of Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, and the UK is to promote the development of offshore renewable energy.

Different from how Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands set the offshore wind farm within their exclusive economic zone, British offshore wind farms are developed under the arrangements of the owner of the seabed, The Crown Estate. Over the years, it has hosted four rental biddings, from the nearest to farthest, smallest to largest, releasing specific marine areas orderly for the developers to apply.

Taking the eastern area of the Irish Sea where offshore wind farms are rather dense as an example, the wind farms are located on the northern and southern sides, and constructions were conducted in multiple stages, allowing the fishermen to adapt to the changes of the fishing grounds while large sea areas are still available for their operations. From the first inauguration of the North Hoyle Wind Farm in 2004 to the completion of the Walney Extension Wind Farm in 2018, around 446 km2 of wind farm areas were developed during the 14 years. Compared to the situation in Taiwan, the energy and fishery authorities have no intention of slowing down the offshore wind farm development at the 440 km2 sea area east of Changhua Wind Farm's sea lane. Offshore wind farm constructions may take up the whole sea area within just 7 to 8 years.

Figure 2: Location map of the offshore wind farm east of the Irish Sea.

Source of the map: https://opendata-thecrownestate.opendata.arcgis.com/datasets/thecrownestate::wind-site-agreements-england-wales-ni-the-crown-estate/explore?location=53.542347%2C2.274556%2C6.54

Viewing from the micro aspect, the communication and contact mechanism between the wind farm developers/operators and the fishermen/fishery groups will be very helpful to reduce the friction from daily operations and establish a beneficial interactive mode during the entire life cycle of wind farms. According to the Fishing Liaison with Offshore Wind and Wet Renewables Group (FLOWW)'s suggestions, the developers should set a fishery liaison plan at the preliminary stage of the development, specifying the appointed Company Fisheries Liaison Officer (CFLO) and the Fishery Industry Representative (FIR), as well as their responsibilities and operations. Every developer should at least hire one CFLO, who should obtain support from the FIR and represent the developer when dealing with fishery issues. The FIR is not required to be an active fishing boat owner/operator, as the most important characteristic of this position is to be trusted by the fishermen. The FIR's responsibility is to reflect fishermen's opinions to the CFLO, who will then forward it to the offshore wind power developer/operator.

The core of the fishery liaison plan is to plan for mitigation and co-existence: during the design process of the entire offshore wind farm, a clear procedure must be present to confirm potential impacts and develop mitigation strategies. The developers should put their primordial goal and main focus on the continuance of fishery activities as much as possible, rather than offering financial compensation. The location and scope of the wind farm, the layout of the wind turbines, and even the landing location of the cables can be included as part of the co-existence plan. Other suggested measures are: solving uncertainties with scientific research and surveillance, increasing fish stocks, improving fishing boats, increasing the profits of fishery activities, developing new fishery modes, establishing fishery community funds, compensating for the interruption of fishery activities, etc.

Conclusion

There is one other uncertainty when it comes to the overlapping of offshore wind farms and fishing grounds: floating wind technology. In Taiwan Strait's contiguous zone, other than the Yunlin-Changhua Ridge (雲彰隆起) area, the water depth is usually between 50~100 meters, and floating piles are more than necessary in these parts. Different from the fixed piles that can be evaded, with all types of floating piles, leg systems, anchor systems, and dynamic cables, what impacts will be faced by the fishery operations? The competent authorities not only failed to promptly propose a demonstration plan to reduce the uncertain factors with empirical data but also have incautiously allowed the development plans fullying adopting the floating wind turbines to enter the EIA, resulting in the developers boasting to their hearts' content as barely any standards are set to assess the quality of their plans. The submarine cables are also another issue that needs to be planned beforehand. As one export cable is required for a 1 GW wind farm, 20 to 30 export cables will certainly pose a great risk for both the fishermen and the developer. The western coastal zone of Taiwan probably won't be able to withstand such intensive cable crossings as well.

Fei-Chun Wu (Researcher/ Taiwan Ocean and Environmental Sustainability Law Center)

Fei-Chun Wu is working as a researcher at the Taiwan Ocean and Environmental Sustainability Law Center, Environmental Rights Foundation. Before joining the TOES Law Center, he had more than a decade of experience as a CSR consultant and understood the different ways of thinking of corporates and NGOs. Wu is interested in exploring the marine social sciences, with a particular focus on human-ecosystem interaction and the trade-off between food, energy and conservation. Given the imperative of a just transition, he believes that ensuring meaningful stakeholder engagement and promoting co-existence between the offshore wind sector and fisheries emerge as critical priorities.

More related articles