From Chemical Reactions to Physical Laws: Carving Out a Non-Mainstream Path for Energy Storage

From Chemical Reactions to Physical Laws: Carving Out a Non-Mainstream Path for Energy Storage

By Xin-En Wu

In the global wave of energy transition , energy storage is widely regarded as the missing piece that determines whether renewable energy can truly become a primary power source. Over the past decade, lithium batteries have risen rapidly, almost becoming synonymous with energy storage itself. Yet as large-scale deployment, long-duration storage, and system safety concerns increasingly surface, the industry has begun to ask a more fundamental question: beyond chemical batteries, is there another path—one that is more stable, more durable, and more aligned with the logic of infrastructure?

Power8 Tech is a company that has deliberately chosen such a "ess mainstream" path.

"There's one fact I've never been able to fully accept," says Edward Ding, Chairman of Power8 Tech. "As long as it's a chemical battery, it ages—whether you use it or not. This isn't a design flaw; it's an inherent limitation of physics and chemistry."

It was precisely this line of questioning that led Ding, at a time when much of the industry was still focused on increasing cell energy density and lowering unit costs, to invest instead in the development of a physical energy storage system based on water and air pressure—eventually giving rise to what Power8 Tech is today.

Ding argues that battery design can return to the most fundamental laws of physics―eschewing chemical reactions altogether and instead storing and releasing energy through pressure conversion between water and gas. By doing so, the system fundamentally avoids the inherent Achilles' heel of chemical batteries: natural degradation over time.

A Materials Scientist's Rebellion: Why Must a "Battery" Be Chemical?

Edward Ding's professional background is deeply rooted in chemistry and materials science. Ironically, it is precisely because he understands these disciplines so well that he sees the limits of chemical batteries with unusual clarity.

"We've grown accustomed to defining technological breakthroughs as 'better materials' or 'more refined structures,'" he explains. "But no matter how much you optimize, the irreversibility of chemical reactions remains."

In Ding's view, once energy storage moves beyond consumer electronics and vehicle batteries into city-scale, industrial-scale, and grid-level applications, the evaluation criteria must be fundamentally rewritten. Cycle life is no longer just about "how many charge– discharge cycles," but whether stable performance can be maintained over twenty or thirty years. Safety is no longer about passing certification tests, but about whether the system remains controllable under worst-case scenarios.

"I started to return to thinking in terms of physical systems," he recalls. "Water, air, pressure, structure— these are engineering elements humans have used for centuries. They don't degrade simply because they sit idle, and they don't suddenly spiral out of control."

Power8 Tech's core architecture is built on this logic. Instead of relying on chemical reactions, energy is stored and released through pressure conversion between water and gas—fundamentally bypassing the Achilles' heel of chemical batteries: natural degradation over time.

Choosing this path, however, meant stepping away from a highly mature supply chain and a technology track favored by both industry and capital markets.

"The biggest challenge was never the technology," Ding admits. "It was market perception and institutional imagination."

In an industry deeply conditioned by lithium batteries, any form of storage that does not look like a battery must pay an additional price to explain itself, to prove itself, and to persuade others. This structural resistance was something confronted Power8 Tech from its earliest days.

In the system's design of Power8 Tech, the air capsule can reach pressures of up to 60 atm. When this pressure is released, the compressed air naturally drives the water within the adjacent capsule, forming a massive 'water bridge'. As the water is expelled and set in motion, it continuously spins turbines, thereby generating electricity.

When Energy Storage Becomes Infrastructure: Longevity, Safety, and System Integration as the Real Bottlenecks

When asked about the key bottlenecks of next-generation energy storage, Ding's answer diverges sharply from prevailing industry narratives.

"Many people point to materials, energy density, or cost," he says. "But in my view, the real bottleneck lies in whether system-level thinking is in place."

System-level thinking, he explains, does not focus on a single battery or a single efficiency metric. It begins with the operational realities of the energy system as a whole: how storage coordinates with the grid, how it integrates into existing buildings and public infrastructure, how it is maintained and managed over decades, and whether it remains controllable under extreme conditions.

"When energy storage evolves from a piece of equipment into infrastructure," Ding notes, "the bottleneck naturally shifts away from materials toward the maturity of integrated system design."

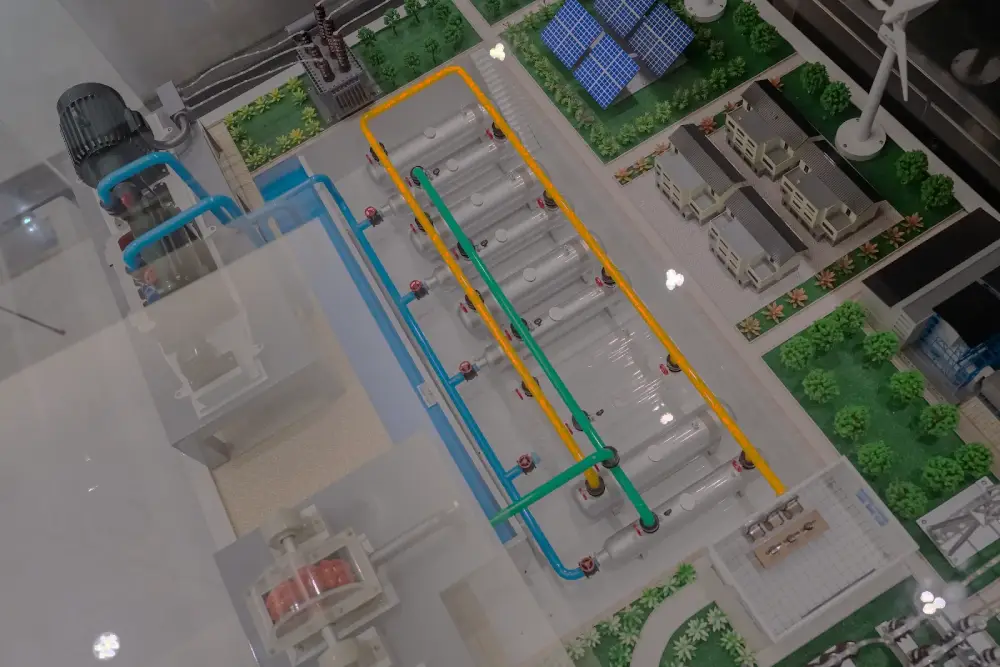

To illustrate what he means, Ding describes one of Power8 Tech's operating systems.

"You can think of it as two capsules," he explains, gesturing as he speaks. "One larger capsule contains air; the smaller one contains water. Air and water operate within a sealed system—there is no chemical reaction, only the conversion of pressure and mass."

In Power8 Tech's design, the air capsule can reach pressures of up to 60 atmospheres. When pressure is released, the compressed air naturally drives the water capsule, creating a massive "water bridge." The flowing water drives turbines continuously, generating electricity.

"This is not small-scale hydropower," Ding emphasizes. "It's artificially created kinetic energy, driven by a single source: pressure."

Total power output is not determined by instantaneous pressure, but by the volume of water—much like a conventional reservoir. As water is released for generation, the water level drops and energy is discharged. To store energy again, the water must be pumped back into the capsule.

This recharge process follows the same logic as pumped-storage hydropower. During periods of surplus electricity—daytime, nighttime, or times of renewable overgeneration—electricity from wind, solar, or other excess sources powers motors and pumps that return the water to the capsule.

"You can think of it as pumping water up to a height of 600 meters," Ding explains. "One atmosphere corresponds to roughly 10 meters of elevation. Sixty atmospheres is equivalent to 600 meters."

As water is pumped back, compressed air returns to the air capsule, restoring the system to a high-pressure state and completing a full cycle.

"This cycle is fixed," Ding says. "You never need to push material limits, and there's no chemical degradation. The entire system obeys just one principle: conservation of mass."

This is why he resists labeling the system as "compressed air energy storage." Instead, he sees it as a closed equilibrium system.

"The ideal gas law is PV = nRT. People ask how n can remain constant when pressure and volume change," he explains. "But in this system, the total amount of air and the total amount of water are fixed. What changes is only their distribution between capsules and the pressure state."

As a result, system lifespan depends not on chemical materials, but on mechanical maintenance—"primarily the motors," as Ding puts it.

What ultimately convinced him of the system's broader potential was not electricity generation alone, but its secondary role in urban environments. During discussions with Farglory Group, the idea emerged of installing the entire system in a building's basement.

"That's when we realized the system inherently provides firefighting capability," Ding recalls.

Power8 Tech's application scenarios have never been confined solely to power system regulation. From the very outset, the stored water within the system itself has been conceived as a strategic backup resource for urban infrastructure, capable of being mobilized in emergency situations.

In extreme situations such as fires, a building may lose all external power, yet the system still retains high-pressure air. Pressure alone can push water upward—without any external electricity—reaching heights of 300 or even 600 meters.

"One floor is roughly three meters. A hundred floors is 300 meters," he notes. "That's well within system capability."

He points out bluntly that firefighting for buildings over twenty stories is, in many respects, an unresolved challenge today. A system originally designed for energy storage thus naturally becomes a piece of safety infrastructure, capable of supporting both energy balancing and fire suppression.

"Fire protection was never our original objective," Ding says. "But it became one of the system's most important auxiliary functions."

As storage is deployed in large buildings, industrial parks, data centers, or urban nodes, isolated performance metrics become secondary. Structural safety, fire integration, maintenance logic, and compatibility with existing infrastructure become decisive considerations.

"No city can afford to replace its core energy storage systems every ten years," Ding states. "Economically, administratively, and politically, it's simply not feasible."

This is why Power8 Tech has positioned itself from the outset as infrastructure-like, rather than as a fast-turnover piece of equipment. The system does not pursue extreme miniaturization, but instead prioritizes structural stability, modular repairability, and predictable lifespan.

From this design philosophy emerges another defining feature: multifunctionality.

Beyond Electricity: Energy Storage as a City's "Second Lifeline"

"At its core, our system is essentially a large water reservoir," Ding explains.

For this reason, Power8 Tech's application scenarios have never been limited to power regulation alone. In emergency situations, the stored water itself becomes a backup resource for urban infrastructure.

"High-rise fires, water outages, disaster response— these are not just energy issues," he says. "They're issues of urban resilience. If a single energy storage system can address multiple needs, why wouldn't you design it that way?"

Under this vision, energy storage is no longer a peripheral component of the grid, but a critical node deeply intertwined with buildings, firefighting systems, and public safety. This perspective also shapes Power8 Tech's focus on dense urban areas, critical facilities, and public buildings.

"In the future, energy storage systems may become part of architectural design—like elevators or water towers today," Ding says. "Not something retrofitted afterward."

Such a shift implies that competition in the energy storage sector will move beyond individual technical parameters toward far more complex cross-disciplinary integration capabilities.

Ding believes that future energy storage facilities will no longer function merely as auxiliary components of the power grid, but will instead become critical nodes deeply integrated with buildings, firefighting systems, and public safety infrastructure.

What a Real Energy Storage Ecosystem Should Look Like

When the conversation turns to business strategy and investment, Ding returns to a personal habit: a long-running reading platform where he has shared weekly reading insights and new knowledge for nearly a decade.

"I've always believed that reading stretches your sense of time," he says. "The more you read, the less likely you are to be dragged around by short-term market sentiment."

This long-term perspective also shapes his view of what a healthy energy storage ecosystem requires. In his assessment, it must include at least three layers: technological diversity, institutional inclusiveness, and patient capital.

"If all resources are concentrated on a single technological path, that in itself becomes a systemic risk," he warns. "Energy transition has never been a single-path problem."

Equally important is whether institutions are willing to leave room for different technologies, rather than forcing new systems into outdated regulatory frameworks. Finally, capital must be willing to accept returns that are slower—but more durable.

"Energy storage is not a trend-driven industry," Ding concludes. "It's much closer to public infrastructure. The choices we make today will shape how cities operate twenty or thirty years from now."

For this reason, Power8 Tech has consistently chosen a path that is quiet, but solid. Not to chase the latest buzzwords, but to answer a more fundamental question: Have we reached a point where an energy system no longer needs constant explanation before people are willing to trust and use it?

More related articles